In the lead-up to World AIDS Day on December 1, Kenya has taken a significant step in the battle against HIV/AIDS by approving the Dapivirine Vaginal Ring (DPV-VR) as a new HIV prevention method for women.

According to Kenya’s Ministry of Health, approximately 1.4 million people in the country are living with HIV, with women accounting for nearly 880,000 of those cases. The new prevention option aims to address the disproportionate impact HIV has on women, particularly those at high risk.

For a 50-year-old single mother from Dandora, Nairobi, HIV is a constant concern. She turned to sex work out of financial necessity and previously relied on daily oral Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) tablets for HIV prevention. However, with the Ministry of Health’s recent approval of the vaginal ring, she is now switching to this new method.

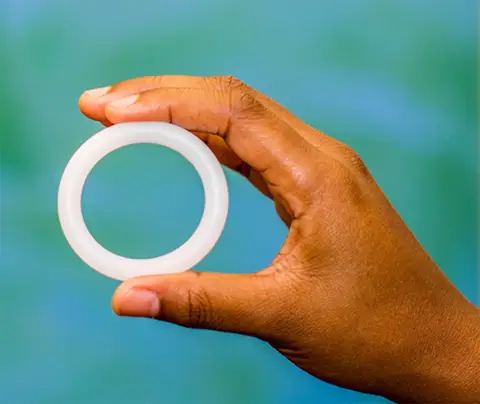

The Dapivirine Vaginal Ring works by releasing the anti-HIV drug dapivirine over a 30-day period. The woman, who requested anonymity due to the social stigma around sex work in Kenya, shared how she learned about the ring from a friend. “I’ve used oral PrEP, but it lacks privacy and can cause side effects. When my friend told me about the vaginal rings, I decided it was a better option to protect myself,” she said.

Kenya began piloting the vaginal ring in June 2023, following its endorsement by the World Health Organization (WHO) in January 2021. The country’s government approved the ring for use in 2022, and it is set to be widely rolled out in 2025, with women able to access it for free.

The ring’s discreetness is one of its key advantages. “With daily PrEP pills, privacy is an issue,” said another Nairobi-based sex worker, also requesting anonymity. “If you have visitors, they might think the PrEP pills are ARVs, and that could lead to judgment. The ring is hidden, and I don’t have to worry about forgetting it like I did with the pills.”

Jennifer Gacheru, a clinical officer at the Bar Hostess Empowerment and Support Programme (BHESP), which supports sex workers, noted that many women prefer the ring due to fewer side effects compared to oral PrEP. “Most of them prefer the vaginal ring because it’s easier to use and doesn’t require remembering to take a pill every day,” Gacheru said.

However, the ring is not effective for all types of sexual activity. It provides protection against HIV during vaginal intercourse but does not offer protection against oral or anal sex. Additionally, it does not prevent other sexually transmitted infections (STIs).

Jonah Onentiah, leader of the HIV Prevention Team at Kenya’s National AIDS and STIs Control Programme (NASCOP), emphasized the need for complementary prevention methods. “We recommend using condoms alongside the vaginal ring to prevent both STIs and pregnancy,” Onentiah said.

Onentiah also pointed to the effectiveness of the ring, which has increased from 27% to 75% when used correctly. “The ring’s discreetness allows women who cannot negotiate condom use to protect themselves from HIV,” he explained.

Users are advised to avoid sexual intercourse for 24 hours after inserting the ring to allow the medication to be fully released.

The Dapivirine Vaginal Ring has already been approved in several other African countries, including Botswana, South Africa, Lesotho, Rwanda, Uganda, Zimbabwe, and Eswatini.

In Kenya, where 9,100 women were newly infected with HIV in 2023, compared to 4,100 men, the introduction of the vaginal ring is seen as a crucial step in reducing new infections among women. Globally, women and girls accounted for 44% of all new HIV infections, according to UNAIDS.

For many Kenyan women, the rollout of the ring in 2025 can’t come soon enough.